Last year’s incomplete property reassessment in New Orleans led citizens and policymakers to question the progress made by the Orleans Parish Assessor on assessment system reforms. BGR evaluated that progress last fall in our report Assessing the Assessor and made recommendations for continued improvement. With the public getting its first look at this year’s assessment rolls beginning July 15, this edition of PolicyWatch re-urges BGR’s recommendations on property valuation practices. It also revisits an unusual funding formula that generates large surpluses for the assessor’s office at the expense of other public entities, many of which face pandemic-related budget shortfalls.

Amy L. Glovinsky, President & CEO

Samuel Zemurray Chair in Research Leadership

On July 15, the Orleans Parish Assessor must open the 2021 property assessment rolls to the public. This will be the public’s first opportunity to review the assessor’s property valuations since last year’s controversial reassessment. The reassessment resulted in substantially higher property values and taxes for thousands of homeowners. However, a Louisiana Legislative Auditor’s report this spring confirmed that the assessor did not complete the reassessment, leaving about 27,000 properties (18% of taxable properties) for revaluation this year. About 57,000 other properties (38%) received land-only reappraisals. The report indicated these properties’ overall valuations may fall below market value.

For this reason, it is important that the assessor demonstrates progress, through the upcoming reassessment, in improving the property valuation process and increasing transparency. To help the public gauge the assessor’s progress, BGR provides the following overview of its key recommendations.

Abandon the practice of “sales chasing” as a method to value property. Through its research, BGR found that the assessor relies heavily on sale prices to value recently-sold properties, a practice referred to as “sales chasing.” While this may seem logical, it is discouraged by national and State standards as it undermines uniformity among property valuations. This is because the assessor uses sale prices to value sold properties and a different method to value unsold properties. This lack of uniformity can distribute the tax burden unfairly among property owners, with newcomers to a neighborhood tending to pay more than long-term property owners.

To test for sales chasing, BGR sampled more than 1,500 detached, single-family residential properties sold in arm’s-length transactions in a 12-month period ending June 30, 2019. It found that the assessor’s office changed the value of nearly 60% of the sold properties to reflect either 90% or 100% of their sale price. Ordinarily, making such post-sale adjustments to just 5% of a sample would raise serious concerns about sales chasing.

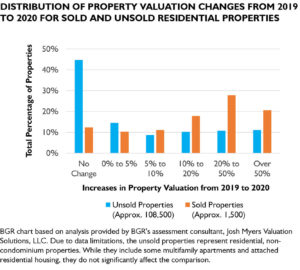

In addition, BGR compared changes in the assessor’s valuations from 2019 to 2020 for the sample of sold properties and for 108,500 unsold residential properties. As shown in the chart, a significantly higher percentage of sold properties had valuation increases greater than 10%. Meanwhile, property valuations for unsold properties were more than three times as likely to remain unchanged. These findings highlight a lack of uniformity in the valuation of sold and unsold properties.

The Legislative Auditor echoed BGR’s findings about sales chasing in its analysis of property valuations. The auditor found that the assessor’s office valued 60% of the approximately 4,000 properties sold in 2019 at either 90% or 100% of the sale price. In making this finding, the auditor noted that the assessor follows a practice of appraising sold properties at 90% of their sale price when the mass appraisal system generates a lower proposed value than the sale price. For the 2020 tax rolls, the auditor found that the assessor’s use of this practice resulted in sold properties valued nearly 15% higher than similar unsold properties.

Consistently use computer-assisted mass appraisal technology in accordance with best practices. Mass appraisal technology uses various sets of data, valuation models and statistical testing to determine property values. It enables an assessor to value large groups of properties at once, while still producing accurate property valuations and adhering to appraisal principles.

BGR sought to gain a more complete understanding of the assessor’s use of mass appraisal technology through an in-person demonstration. However, the assessor denied BGR’s request. This lack of transparency and the assessor’s inability to complete the parishwide reappraisal last year raise concerns about whether the office is properly utilizing mass appraisal technology to determine property values. BGR calls for the assessor to demonstrate to the public how the office uses this technology as part of a comprehensive explanation of how the office values properties.

The Legislative Auditor found that the assessor did not reappraise some neighborhoods because the office was not comfortable with the accuracy of the valuations its mass appraisal models produced. Due to time constraints, the assessor did not attempt to solve the valuation or modeling issues, leaving these neighborhoods for revaluation this year.

BGR recommends that the assessor make this information public to inform residents about the reassessment process and potential changes to property valuations, assessments and the calculation of property taxes.

Conduct annual studies to check the accuracy of the office’s property valuations and share the findings with the public. Best practices strongly encourage assessors to self-monitor their appraisal performance by conducting ratio studies. These studies, which compare an assessor’s valuations to real estate market data through various statistical calculations, can gauge an assessor’s appraisal accuracy and uniformity, among other things.

The assessor told BGR that the office conducts such studies, but did not provide a full copy of any study from prior years. BGR recommends that the assessor conduct these studies on an annual basis to check the office’s appraisal performance. BGR also recommends that the studies include a sales chasing analysis so the public can see whether the office has stopped using this practice.

Further, to increase transparency, BGR recommends that the assessor share the office’s findings with the public to inform residents and policymakers about the office’s appraisal performance, property valuations and market conditions.

“BGR’s recommendations from Assessing the Assessor offer a roadmap to a fairer and more transparent assessment system this year and beyond.”

Collectively, the weaknesses identified in BGR’s and the Legislative Auditor’s reports highlight fundamental concerns about how the assessor’s office is utilizing its mass appraisal technology. Purchased for $1.2 million more than a decade ago, the technology was intended as an investment in a modernized system that could value property in accordance with appraisal industry standards and best practices. Taxpayer support for the system continues today through technology-related contracts and staff salaries. As such, the assessor’s office should use the technology properly to produce fair and accurate property valuations and show the public the effectiveness of its technology investment.

BGR’s recommendations from Assessing the Assessor offer a roadmap to a fairer and more transparent assessment system this year and beyond. As New Orleans real estate faces an uncertain long-term impact from the public health and economic crises, it is all the more essential for the assessor to have clear, well-supported valuation practices to fairly handle the challenges of future reassessments.

The economic fallout from the ongoing public health crisis has left the City of New Orleans, NOLA Public Schools and other local taxing bodies grappling with significant funding shortfalls. By contrast, the Orleans Parish Assessor’s Office anticipates its 2020 tax revenues will increase by $1 million (about 8%) to $13 million. Moreover, the assessor has accumulated $23 million in reserves, which is more than two-and-a-half times the office’s annual operating costs. These sizable reserves are linked to a problematic funding formula that BGR has urged policymakers to reevaluate.

Based on a State-mandated formula unique to Orleans Parish, the assessor’s office receives a fee equal to 2% of the total amount of property taxes billed each year. The fee will generate 96% of the office’s total revenue this year. As the parish tax collector, the City deducts the assessor’s fee, along with its own fee equal to 2% of taxes collected, from tax payments before distributing the net revenue to property tax recipients. The assessor’s fee will reduce this year’s estimated tax receipts for the four largest property tax recipients by the following amounts: the City ($5.6 million), NOLA Public Schools ($3.6 million), the Sewerage & Water Board ($1.3 million) and the Orleans Levee District ($870,000).

BGR has raised concerns about the assessor’s funding mechanism because the fee is not based on the office’s workload or expenditures. Rather, the fee grows along with increases in millage rates and property valuations. For example, a 2.5-mill tax that voters approved a few years ago for fire protection increased the assessor’s funding by about $200,000 per year, even though the office’s workload did not change as a result of the new tax.

Other assessors’ offices in Louisiana are funded either by a dedicated millage or by a legislatively-determined amount paid by all taxing entities on a pro-rata basis. A dedicated millage differs in two key ways from the fixed percentage of billed property taxes that the Orleans assessor receives. First, a millage is subject to rollback requirements when property valuations increase. Second, unlike a fixed percentage, a millage does not generate additional revenue when other entities impose new property taxes. Both characteristics could help control growth in the assessor’s reserves.

Since BGR first flagged the size of the assessor’s reserves in a 2015 report , the reserves have more than doubled as shown in the chart. The pace of growth has accelerated in recent years, with increases of $5 million and $4.5 million in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Based on information the assessor provided BGR, the office projects minimal growth in reserves this year. This is because the assessor plans to provide the City $3 million toward the purchase of a new revenue collection system. Absent this allocation, the assessor’s reserves would grow by a projected $3 million. The assessor says the new system will not only help the City, but also benefit the office by providing updated information on businesses, personal business property and occupational licenses.

After BGR called for a review of the funding formula, the assessor refunded $2.2 million of the office’s surplus revenue to the City in 2016. The City then distributed the revenue to local property tax recipients on a pro-rata basis. The assessor, however, has not made any refunds since then. Such refunds of excess revenue are at the assessor’s sole discretion. If the assessor refunded the $4.5 million in surplus revenue from 2019, the largest property tax recipients could expect to receive the following amounts: the City ($2 million), NOLA Public Schools ($1.3 million), the Sewerage & Water Board ($450,000) and the Orleans Levee District ($305,000).

The assessor is in discussions with the judges of Orleans Parish Civil District Court about a joint facility that would also house the Clerk of Civil District Court, the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s civil division and the judges, clerk and constable of First City Court. The parties recently began exploring a potential renovation of the City-owned former Veterans Affairs hospital site. The judges do not yet have an estimate of what such a renovation would cost. They also continue to consider renovating their existing courthouse adjacent to City Hall. A 2016 feasibility study estimated this could cost roughly $65 million, although this amount would depend on the ultimate scope of the project.

A fund to build a new courthouse or to renovate an existing site contains about $11.6 million from a special document filing fee collected by the civil clerk’s office. The fee generates about $1.5 million a year. The fund would be in addition to any contribution from the $10 million the assessor has set aside. The judges said they are in discussions with the City to potentially issue bonds to finance a renovation, with the building’s occupants paying off the bonds.

The civil clerk’s office has $25.7 million in reserves, or about 175% of its operating budget. However, the clerk’s budget assigns all of the reserves to various purposes and projects. This includes $17.4 million set aside to cover accrued post-employment benefits, such as pensions and health insurance, in case future revenues are insufficient to cover these costs. The office is not required to maintain these reserves. This is a belt-and-suspenders budgetary approach that few government entities could afford. For example, the City would have to set aside more than $1 billion to cover its accrued post-employment benefits. The clerk’s office told BGR that it is in the process of evaluating the extent of any future contributions that it might make to the courthouse project above the statutorily-required special filing fee. The factors the clerk will consider include, among other things, the cost of the project, the size of the space allocated to the clerk’s office, the level of contributions by other occupants and whether the court entities could relocate to a potential new City Hall.

“The excess funding that the assessor’s office has set aside for new office space is revenue that would otherwise have gone to property tax recipients, many of which are struggling financially.”

The potential renovation is in the early stages and BGR has not taken a position on its merits. However, the problematic funding formula for the assessor’s office raises questions about its participation in the project. The excess funding that the assessor’s office has set aside for new office space is revenue that would otherwise have gone to property tax recipients, many of which are struggling financially. A refund from the assessor’s reserves could help these entities deal with the crisis. Because of this, the assessor should demonstrate that the new office space is a top community priority before participating. If the project does eventually move forward with the assessor’s participation, any contribution by the assessor should take into account the portion of the office space the assessor would utilize. Based on space estimates the judges provided BGR, the assessor’s office would occupy less than 10% of a joint facility.

Going forward, as BGR recommended in Assessing the Assessor, State and local policymakers should review the assessor’s unusual funding mechanism to better align it with the office’s needs. Given the excess revenue generated by the assessor’s fee, such a review is essential to ensure the efficient use of limited public resources. This is particularly important as the City, NOLA Public Schools, the Sewerage & Water Board and other local taxing bodies face revenue shortfalls related to the public health crisis or seek additional revenue to address high-priority needs.

Click below to join our email list to receive this free newsletter and notices of other reports, events and news from the Bureau of Governmental Research.

Property taxes are a basic means of financing local government, but the public faces a confusing array of tax rates, taxing bodies and dedicated purposes across the New Orleans region. To help explain these taxes, the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) today launched an interactive, online tool. BGR’s property tax dashboards for Jefferson, Orleans, and St. Tammany […]

In a November 28 letter to the City Council, BGR recommends that the council create a formal process to objectively evaluate S&WB funding proposals for the city’s water, sewer and drainage systems. BGR also recommends that the council develop a stronger framework for oversight that relies more on regular accountability, instead of the council’s control […]

This BGR NOW report urges the City of New Orleans and the Orleans Parish Sheriff to resolve a long-running disagreement over funding the jail. The dispute flared anew last fall when the City Council denied the Sheriff’s request for a $12.4 million funding increase. Voters subsequently rejected a Sheriff’s Office proposal to increase its property […]

OVERVIEW These On the Ballot reports inform New Orleans voters about three propositions on the October 14, 2023 ballot: the renewal of a property tax for public school facilities and charter amendments on code enforcement and the City budget process. The Orleans Parish School Board is seeking to renew a property tax of up to 4.97 […]

OVERVIEW This On the Ballot report studies the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s proposed property tax increase that New Orleans voters will decide on April 29, 2023.

OVERVIEW This report is intended to help New Orleans voters make an informed decision on whether to approve a new 5-mill, 20-year property tax dedicated to programs and capital investments that provide childcare and educational opportunities for children who have not yet entered kindergarten.

OVERVIEW On the Ballot: New Orleans Library and Housing Taxes, December 11, 2021 provides New Orleans voters with independent analysis of the library and housing property tax propositions on the December 11 ballot citywide. Both taxes would take effect in 2022 and run for 20 years. Each would replace an existing property tax that expires […]

OVERVIEW In August, the New Orleans City Council excluded hotel room rentals from a new sales tax for enhanced public safety in the French Quarter despite questions about whether the exclusion is permissible under state law. While BGR has not taken a position on the legal issues, this BGR NOW report identifies several compelling policy […]

OVERVIEW BGR’s report, On the Ballot: French Quarter Sales Tax, April 24, 2021, is intended to help French Quarter voters make an informed decision on a proposition for a 0.245% sales tax to pay for supplemental police patrols and other public safety services. The tax would take effect July 1 and remain in place for […]

OVERVIEW On the Ballot: French Quarter Sales Tax Renewal, December 5, 2020 is intended to help French Quarter voters make an informed decision on a proposition to renew a 0.2495% sales tax to pay for supplemental public safety services. The proposition would extend the tax – set to expire at the end of 2020 – for […]

OVERVIEW On the Ballot: New Orleans Property Tax Propositions, December 5, 2020 analyzes three propositions to replace several City of New Orleans property taxes that expire at the end of 2021. The replacement taxes would have the same combined rate of 5.82 mills as the existing taxes. However, the propositions would change the tax dedications. […]

OVERVIEW With the public getting its first look at this year’s property tax assessment rolls beginning July 15, 2020, this edition of PolicyWatch re-urges BGR’s recommendations on property valuation practices in New Orleans. It also revisits an unusual funding formula that generates large surpluses for the Orleans Parish Assessor’s office at the expense of other […]

OVERVIEW Welcome to the inaugural edition of PolicyWatch, a periodic newsletter that draws on BGR’s body of independent, nonpartisan research to address current public policy issues. This edition focuses on the City of New Orleans’ finances as it faces a pandemic-induced budget deficit. It discusses the City’s proposal to borrow up to $100 million as […]

OVERVIEW Assessing the Assessor: Progress on Property Assessment Reform in New Orleans evaluates whether and to what extent New Orleans’ property assessment system has improved under the single parish assessor since he replaced the seven-assessor system in 2011.

OVERVIEW As the City Council reviews the proposed $722 million 2020 operating budget, BGR Now: A Framework for Assessing New Orleans’ Proposed 2020 Budget outlines key findings of BGR’s recent City budget study to help inform citizens and policymakers. BGR’s study, A Look Back to Plan Ahead, analyzes growth in revenues and changes in expenditures […]

Overview On the Ballot: New Orleans Bond and Tax Propositions, November 16, 2019 studies three propositions to let the City issue bonds for capital improvements, levy a new tax for maintenance, and levy a new tax on short-term rentals. If voters approve, the City of New Orleans would be able to: Issue up to $500 […]

Overview A Look Back to Plan Ahead: Analyzing Past New Orleans Budgets to Guide Funding Priorities reviews a decade of City General Fund budgets. It also lays a foundation for examining potential opportunities to reallocate revenue to critical needs.

Overview On the Ballot: Housing Tax Exemptions in New Orleans, October 12, 2019 reviews Constitutional Amendment No. 4, which would allow the City of New Orleans to exempt from taxation properties with up to 15 residential units located within Orleans Parish to promote affordable housing. This report is the latest in BGR’s On the Ballot series, […]

Overview The $1 Billion Question Revisited: Updating BGR’s 2015 Analysis of Orleans Parish Tax Revenues breaks down 2019 projected local tax revenue by recipient and by purpose to help assess current funding priorities and identify options to redirect tax revenues to needs.

Overview The report analyzes a May 4, 2019 tax proposition in New Orleans to replace three existing taxes for parks and recreation totaling 6.31 mills with a single tax at the same rate. Voter approval would not result in a tax increase. The three existing taxes fund the Audubon Zoo (0.32 mills), the Audubon Aquarium […]

Overview On March 30, 2019, New Orleans voters will decide whether to approve a new property tax for elderly services, programs and other assistance. If approved, the tax will be levied citywide at a rate of 2 mills for five years, beginning in 2020. The tax would generate $6.6 million in the first year. BGR’s […]

Overview In this report, BGR compares Orleans Parish hotel taxes to best practices for taxation as well as state and national norms, focusing primarily on the share of revenue available for general municipal purposes.

OVERVIEW This On the Ballot report reviews a constitutional amendment on the November 6, 2018 ballot that would allow eligible homeowners to phase in an increase in property taxes resulting from a reappraisal. The four-year phase-in process would apply only to residential properties subject to the homestead exemption that increase in assessed value by more […]

OVERVIEW This report is the latest installment in BGR’s Candidate Q&A Election Series. The new report consolidates and reissues the responses of the newly elected City of New Orleans mayor and councilmembers who completed BGR’s surveys last fall on important issues facing City government. We encourage citizens to revisit the issues by reviewing the BGR […]

Overview BGR’s On the Ballot report analyzes the proposed 10-year renewals of three existing property taxes for New Orleans public schools that voters will decide on October 14, 2017.

Overview For the October 14, 2017 primary elections in New Orleans, BGR provided voters with its 2017 Candidate Q&A Election Series. BGR submitted questions to all mayoral and City Council candidates on public safety, infrastructure and other important public policy issues facing the City of New Orleans government. BGR compiled the answers of the candidates who […]

Overview Paying for Streets: Options for Funding Road Maintenance in New Orleans explores ways to fund the routine maintenance necessary to safeguard the City’s $2 billion, once-in-a-lifetime capital investment in the street network.

Overview Beneath the Surface: A Primer on Stormwater Fees in New Orleans explores a funding mechanism for drainage that is expanding in usage nationwide as an alternative to ad valorem property taxes.

Overview BGR reviews two property tax propositions on the ballot in New Orleans on December 10, 2016: a tax increase for fire protection services for the City of New Orleans and a tax renewal for the Sewerage & Water Board’s drainage system.

Overview In Convention Center Bill Highlights Need to Rethink Local Taxation, BGR addresses a bill that would grant taxing authority to the New Orleans Ernest N. Morial Convention Center’s economic development district. The release calls for a comprehensive re-evaluation of Orleans Parish taxes, with an eye toward aligning tax revenues with the city’s most pressing needs.

Overview BGR explains and analyzes two tax propositions in New Orleans on April 9, 2016: one for street work and other improvements, and a second for the police and fire departments.

Overview In The $1 Billion Question: Do the Tax Dedications in New Orleans Make Sense? BGR presents a comprehensive picture of where local tax dollars are going in Orleans Parish. The report provides breakdowns of tax dedications by entity and by purpose, and gives examples of problems that can arise when tax dedications are established […]

Overview BGR analyzes two property tax propositions meant to sustain west bank flood protection systems and three proposed St. Tammany charter amendments before voters on November 21, 2015. The tax propositions include a new tax for the West Jefferson Levee District and a tax renewal for the Algiers Levee District in New Orleans. Both levee […]

Overview This On the Ballot report informs voters in the October 24, 2015 election about a proposed quarter-cent sales tax for public safety in New Orleans’ French Quarter and a constitutional amendment allowing the State of Louisiana to invest in an infrastructure bank.

Overview BGR analyzes proposed property taxes for the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Law Enforcement District, the New Orleans Public Library system and the Lake Borgne Basin Levee District in St. Bernard Parish. Voters in New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish will decide the propositions on May 2, 2015. The Lake Borgne Basin Levee District is governed […]

Overview BGR reviews a proposed property tax for the upkeep of public school facilities in New Orleans and 11 propositions to amend the Jefferson Parish charter that voters will decide on December 6, 2014. The charter propositions relate to: Modifying the Jefferson Parish Council’s authority to investigate parish affairs Limiting the outside employment of the […]

Overview BGR examines two proposed amendments to the Home Rule Charter of the City of New Orleans, one Orleans Parish property tax proposition and two constitutional amendments on the ballot for November 4, 2014. One City charter amendment would incorporate certain professional services contracting reforms made in 2010. The other charter amendment would move the […]

On July 22, 2014, hundreds of citizens and a number of government officials turned up at a citywide meeting hosted by the Fix My Streets campaign and the Lakeview Civic Improvement Association to discuss options for addressing New Orleans’ bumpy street network. The dialogue centered on the need to determine the condition of city streets, […]

Overview In this release, BGR examines a 2013 legislative proposal to authorize a hotel assessment in New Orleans. For hotel guests, the assessment would be the functional equivalent of a new hotel tax.

Overview In On the Ballot: November 6, 2012, BGR examines three proposed constitutional amendments, two propositions pertaining to multiple parishes in the New Orleans area, a proposed change to the City of New Orleans charter and two local tax propositions. The three constitutional amendments would strengthen gun rights, provide an additional homestead exemption to spouses […]

Overview BGR examines charter amendments, tax propositions and state constitutional amendments on the October and November 2011 ballots. The October 22 ballot includes a Jefferson Parish charter amendment to establish the Office of Inspector General and an Ethics and Compliance Commission, as well as a related property tax to fund both entities. It also includes […]

Overview The Bureau of Governmental Research made presentations before the New Orleans Tax Fairness Commission on February 3, 2011 and February 23, 2011. The first presentation, Taxation in New Orleans, examines the City’s tax picture, with particular emphasis on property taxes. It provides an overview of the tax structure and discusses issues related to exemptions […]

Overview On November 24, BGR sent a letter to the Mayor and City Council on the proposed 2011 budget for the City of New Orleans. The letter contains suggestions that would free up millions of dollars.

Overview In Rolling Forward: The Complete Picture, BGR provides a composite picture of citywide property tax rates in New Orleans, the capacity of various taxing entities to increase those rates, and the potential cost to property owners. The report also explains the “roll forward” process following a property assessment.

BGR analyzes 10 State constitutional amendments on the ballot for November 2, 2010. The amendments concern a wide variety of issues, including: Salary increases for elected officials Allocation of State of Louisiana severance taxes Property tax exemption for disabled veterans Limiting tax increases for non-elected taxing authorities Extending the period following a disaster for retaining […]

Overview In The Price of Civilization: Addressing Infrastructure Needs in New Orleans, BGR provides information on New Orleans’ core infrastructure needs – including streets, the systems of the Sewerage & Water Board of New Orleans, schools and the Orleans Parish jail – and assesses the community’s capacity to fund those needs.

Overview In Forgotten Promises: The Lost Connection Between the Homestead Exemption and the Revenue Sharing Fund, BGR examines the decline of the State of Louisiana’s funding mechanism for compensating local taxing bodies for the costs of the homestead exemption. The report provides data on compensation for New Orleans, Jefferson Parish and St. Tammany Parish.

Overview As the campaign for the city’s soon-to-be consolidated assessor’s office begins, BGR releases In All Fairness: Building a Model Assessment System in New Orleans. The report explains what the new citywide assessor must do to create a fair, efficient and transparent property tax assessment system in Orleans Parish.

Overview BGR provides analysis of local propositions as well as amendments to the state constitution appearing on the ballot for November 4, 2008. A proposition in New Orleans would amend the city charter to make comprehensive changes to planning and land use decision making in the city. A proposition in Jefferson Parish would expand the permissible […]

Overview Street Smarts: Maintaining and Managing New Orleans’ Road Network provides an overview of street management systems in general and examines the challenges New Orleans faces in maintaining its streets. It concludes with recommendations to improve street maintenance and management in New Orleans.

Overview In On the Ballot: New Orleans, October 2008, BGR provides analysis and takes positions on two ballot propositions: one to issue bonds through the Sheriff’s Law Enforcement District for Orleans Parish criminal justice facilities and another to protect the newly created Office of Inspector General in New Orleans.

Overview On the Ballot: Orleans Parish School Tax Renewals provides an overview of four New Orleans school property tax millages up for voter renewal on July 19, 2008. The taxes support basic operations and maintenance, among other needs.

Overview BGR provided this piece for publication in Gambit Weekly, explaining the ways in which significantly increased property tax assessments in New Orleans can be about fairness and the common good.

Overview This On the Ballot report analyzes proposed constitutional amendments of particular significance to the New Orleans region. This issue covers amendments before voters on November 7, 2006. This report focuses on five amendments that address issues relevant to the New Orleans area. These amendments deal with property taxes, the juvenile court system, and assessors. […]

Overview BGR sets forth reasons for pursing the consolidation of New Orleans’ seven-assessor system post-Katrina as an important step toward establishing a fair system of property tax assessments. This report is part of a series of web-based reports BGR began publishing following the 2005 Hurricane Katrina disaster.

Overview In this release, BGR finds inequities in assessors’ disaster-related adjustments to property tax assessments post-Katrina. This is part of a web-based series of reports on the rebuilding of New Orleans following the 2005 Hurricane Katrina disaster.

Overview In New Orleans, too many property owners pay little or no taxes on their properties; exemptions are granted regardless of need; and, as a result of inconsistent assessments, properties of similar value bear widely different tax burdens. In this report, BGR illustrates the impact of under-assessments and excessive exemptions on local governments and taxpayers […]

Overview BGR analyzes two of four state constitutional amendments that will appear on the November 2, 2004, ballot. The two amendments would modify the homestead exemption and the veterans’ preference to apply for civil service positions. In addition, BGR provides voters in New Orleans with information on a proposed $260 million bond issue and Jefferson […]

Overview On February 2, 2002, the voters of New Orleans will consider a proposition to authorize the extension of the property tax millage for the New Orleans Business and Industrial District. The district has since been renamed the New Orleans Regional Business Park.

Overview This report presents BGR’s analysis of the Downtown Development District’s tax and bond proposal on the ballot for April 7, 2001 in New Orleans.

Overview This report presents BGR’s analysis of ballot propositions to allow the issuance of general obligation bonds of $150 million by the City of New Orleans and $27 million by the Orleans Parish Law Enforcement District. Although the Criminal Sheriff governs the district, the bond proposal would raise funds for the sheriff, the district attorney […]

Overview This issue of the Outlook series examines the capital budget process of the City of New Orleans and critiques the implementation of the 1995 voter-approved building program.

Overview This report examines property tax exemptions and assessment administration in Orleans Parish. It provides a breakdown of government, nonprofit, homestead and other exemptions. It further reviews the administration of property tax assessments by New Orleans’ seven assessors. To view sources consulted, click here.

Overview This report provides a short analysis of the potential creation of three separate neighborhood-based special tax districts in New Orleans and a recommendation on two proposed amendments to the Louisiana Constitution relative to the governance of higher education. The neighborhood districts will provide additional funding for enhanced security and in some cases, beautification and […]

Overview This report provides a short analysis of the proposal to levy a one-mill ad valorem property tax in New Orleans to fund the offices of the Orleans Parish Assessors.

Overview This report provides a synopsis and short analysis of all 18 proposed amendments to the Louisiana Constitution on the October 3, 1998, election ballot. The topics include assessment freezes for senior citizens and properties undergoing restoration, as well as parish severance tax allocations and remediation of blighted property: Establishes community college system Increases parish […]

Property taxes are a basic means of financing local government, but the public faces a confusing array of tax rates, taxing bodies and dedicated purposes across the New Orleans region. To help explain these taxes, the Bureau of Governmental...

In a November 28 letter to the New Orleans City Council, BGR expressed concern that the council does not have a formal process to evaluate funding requests from the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans (S&WB). The lack...

The Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) published a report today calling on the City of New Orleans and the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office to resolve a long-running disagreement over funding for the parish jail. The dispute flared anew last fall...

Today, the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) releases three On the Ballot reports for the October 14 election. The reports are intended to help New Orleans voters make informed decisions on three separate propositions: a property tax renewal for...

Spanish Plaza, the public space at the foot of Canal Street that New Orleans officials have long worried was neglected and underused, would get a new event space for musicians and other improvements through a new, tax-funded plan working...

The New Orleans City Council on Thursday asked state authorities to review whether Assessor Erroll Williams’ office properly conducted a recent citywide reassessment, citing findings that the assessor used “sales chasing” during the last quadrennial assessment. Williams has long...

Orleans Tax Assessor Erroll Williams took part in a Q&A session with the New Orleans city council on property assessments. Williams said he disagrees with a Bureau of Governmental Research reports that said he assigns property values by chasing...

Following a 23 percent spike in citywide property values in a recent property tax reassessment, the New Orleans City Council — along with a few other local agencies that collect property taxes including the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office and...

The citywide assessment of New Orleans property values is set to give homeowners sticker shock this month as they receive letters from the Orleans Parish Assessor’s Office showing a potentially huge jump in property taxes. Assessor Erroll Williams said...

If you’ve opened your letter from the Orleans assessor’s office, you may have experienced a bit of sticker shock. Property values are reassessed every four years, and this time they have gone up for many homeowners. So, what you...

Orleans Parish Sheriff Susan Hutson’s proposal to double her office’s property tax millage didn’t just go down to defeat on April 29. Voters opposed her proposition by the largest margin in memory — 91% voted against it. That’s more...

New Orleanians of every stripe can all agree on maybe just a few things. Crawfish are good. Potholes are bad. The refs have it in for the Saints. Saturday’s election results may add another item to the list. More...

NEW ORLEANS (WVUE) – Voters in Orleans and St. Tammany parishes overwhelmingly rejected property tax hikes Saturday (April 29) that had been championed by Sheriff Susan Hutson and Coroner Dr. Charles Preston, respectively. A measure to nearly double the...

New Orleans on Saturday delivered a nearly unanimous rejection of a proposal from Orleans Parish Sheriff Susan Hutson to nearly double a tax her office collects, the latest in a series of setbacks for Hutson that comes almost a...

Voters are going to the polls across Southeast Louisiana today consider tax issues and a handful of races. Elections got underway this morning in Orleans, St. Tammany, Plaquemines, and St. John the Baptist parishes. New Orleans voters are deciding...

New Orleans voters will decide the fate Saturday of a tax proposition that would nearly double the tax collected by the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office. The tax call in New Orleans highlights an otherwise slim ballot across the metro...

Tomorrow is the first Saturday of Jazz Fest. It’s also Election Day in New Orleans — but we doubt very many voters will queue up to cast a ballot. That’s too bad, because Orleans Parish Sheriff Susan Hutson is...

PW Law Enforcement District5.5 Mills In-Lieu – Sheriff – 10 Yrs.Shall the Law Enforcement District of the Parish of Orleans, State of Louisiana (the “District”), levy a tax of 5.5 mills on all property subject to taxation in the...

On April 21, 2023, BGR President and CEO Rebecca Mowbray and Research Analyst Paul Rioux discussed BGR’s report, On the Ballot: Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office Tax, April 29, 2023, with Dr. Torin Sanders on The Good Morning Show on...

The International Association of Chiefs of Police has been conducting meetings across New Orleans this week to receive public comment on what citizens want to see in their next police Chief. NOLA Messenger queried more than a dozen residents...

NEW ORLEANS — On April 29, property owners in Orleans Parish will have to decide on a millage that would increase property taxes to better staffing and conditions at the Orleans Parish jail. If approved, the millage would increase...

NEW ORLEANS (WGNO)— May 2 will mark one year since Orleans Parish Sheriff Susan Hutson took office and Thursday, she reflected on her first year. “In the first week, we had an officer-involved shooting. We had a fake escape,...

Newell speaks with Rebecca Mowbray and Paul Rioux of BGR about Sheriff Susan Hutson’s push for higher property taxes to increase her agency’s budget being too vague. Click this WWL Radio link to listen to the segment. Click here...

Independent watchdog group Bureau of Governmental Research says they are against the millage to increase property taxes to fund jail.

NEW ORLEANS — The Bureau of Governmental Research has issued a report that does not support the recent proposed tax increase from the Orleans Parish Sheriff. Voters will decide whether or not to nearly double a $2.8 million tax...

NEW ORLEANS — From the Bureau of Governmental Research: On April 19, BGR released a report intended to help Orleans Parish voters make an informed decision on whether to nearly double a 2.8-mill tax for the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office by...

Orleans Parish Sheriff Susan Hutson’s proposal to nearly double a tax her office collects is premature, skirts the practices of other large parishes and remains short on details just 10 days ahead of the April 29 referendum, an independent...

NEW ORLEANS (WVUE) – Sheriff Susan Hutson’s push for higher property taxes to increase her agency’s budget should be rejected by voters because her plans for spending the windfall are too vague, a non-partisan New Orleans policy research group...

ORLEANS PARISH, La. (WGNO) — “What is the timeline for all these investments? Why are they priorities? Which ones are the biggest priorities on here? I don’t really know,” questioned Becky Mowbray. She’s the president and CEO of the...

Today, the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) releases a new report, On the Ballot: Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office Tax, April 29, 2023. The report is intended to help Orleans Parish voters make an informed decision on whether to nearly...

Just a few months after the New Orleans City Council rejected Orleans Parish Sheriff Susan Hutson’s request for a $13 million budget hike, Hutson is again seeking millions in new funding. This time, the proposal has flown below the...

Awards The Bureau of Governmental Research has received two research awards from the Governmental Research Association. BGR received a Certificate of Merit for Distinguished Research on a Local Government Issue for its method of analyzing local tax propositions in its “On...

NEW ORLEANS — From the Bureau of Governmental Research: BGR received two research awards from the Governmental Research Association at a national conference held last month in Philadelphia. In addition, BGR recently welcomed Melanie Bronfin as a new member of its...

The Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) recently received two research awards from the Governmental Research Association (GRA) at its national conference held last month in Philadelphia. In addition, BGR recently welcomed Ms. Melanie Bronfin as a new member of...

Voters in New Orleans on Saturday approved a property tax measure aimed at creating 1,000 or more early childhood seats for low-income children. Support for the 20-year, 5-mill tax ran at 61% to 39% with all 351 precincts reporting,...

New Orleans voters will see just one item on Saturday’s ballot: a millage proposal to fund early childhood education. We break down what you need to know before you head to the polls. Dates, times and locations to knowElection...

New Orleans voters are being asked this month to approve a property tax to create 1,000 or more early childhood seats for low-income children under age 4. Supporters cast the April 30 ballot proposition as a transformational plan to...

Voters in three area parishes are being asked to enact new taxes on April 30; early voting begins Saturday. We understand that it might seem odd to ask voters to raise taxes in 2022, when governments are bulging with...

NEW ORLEANS — From the Bureau of Governmental Research: BGR has released a new report intended to help New Orleans voters make an informed decision on whether to approve a new 5-mill, 20-year property tax dedicated to programs and capital investments...

Today, the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) releases a new report, On the Ballot: Early Childhood Education Property Tax, New Orleans, April 30, 2022. The report is intended to help New Orleans voters make an informed decision on whether...

A local property tax dedicated to affordable housing and blight reduction is set to expire at the end of the year, after a majority of New Orleans voters rejected a ballot proposition to renew it earlier this month. The...

When Marlin Gusman was elected to the New Orleans City Council more than two decades ago, Oliver Thomas was already there. Their paths would diverge, with Gusman moving up to run the city’s jail for 17 years as sheriff...

New Orleans voters approved a ballot measure to fund the Public Library system on Saturday, but a second tax proposition — to pay for an affordable housing and blight elimination fund — was narrowly defeated. Property owners have already...

New Orleans voters on Saturday narrowly rejected the renewal of a 0.91-mill property tax housing programs that had been in effect since 1991. The “no” vote prevailed with less than 51%, and the 940-vote difference amounted to 1.7% of...

New Orleans voters will head to the polls on Saturday with four City Council seats at stake along with a hotly contested race for Orleans Parish sheriff. Live election results: New Orleans sheriff, St. Tammany casino and more In...

Public library millage renewal: Yes In 2020, voters soundly rejected a complicated property tax swap that would have cut deeply into the New Orleans Public Library system’s bottom line. We too were skeptical that this vital institution could do...

New Orleans voters will decide Saturday whether to renew a tax that largely funds the city’s public library system, roughly a year after they rejected a tax plan that would have cut library funding. The 4-mill tax on Saturday’s...

New Orleans residents will head to the polls on Saturday to decide whether to renew two existing property taxes that expire at the end of the year — one that brings in roughly $10 million per year for the...

New Orleans voters will decide Saturday whether to continue paying a $4 million property tax for housing assistance. The 0.91-mill levy is relatively small compared to other citywide property taxes, but housing advocates say it provides important financing to...

New Orleans voters will consider two property tax proposals Saturday, one dedicated to the city’s library system and the other for a key housing fund. Both are intended to replace existing millages that expired at the end of the...

The Bureau of Governmental Research has published its report on two tax propositions under consideration in the New Orleans city elections taking place on December 11th. One proposition would help fund the New Orleans Library System, and the other...

Last year, New Orleans voters soundly rejected a complicated property tax swap that would have cut deeply into the New Orleans Public Library system’s bottom line. We too were skeptical that this vital institution could do more with less....

Early voting in the Dec. 11 runoff elections for New Orleans City Council, Sheriff and Clerk of Criminal Court begins Saturday, and voters will also weigh in on tax propositions for the New Orleans Public Library and housing. The...

Early voting for the Dec. 11 municipal runoff begins Nov. 27 in the (thankfully) final election of the year. Voter turnout tends to be pitifully low in December elections, even when the stakes are high. This year’s election will...

New Orleans voters will find themselves inside a voting booth for the second month in a row this December, with two millages and six runoff races to decide on. The quick turnaround from the Nov. 13 election coupled with...

A prominent government watchdog group is recommending New Orleans voters renew one expiring property tax on the Dec. 11 ballot but reject another. In a report published Monday, the Bureau of Government Research supports renewing a 4-mill tax for...

The nonpartisan think tank the Bureau of Governmental Research released a new report on Monday with a split decision on the two property tax renewals that New Orleans voters will decide on during the Dec. 11 election. BGR is...

A nonpartisan policy group is split on its opinion of two tax proposals New Orleans voters will consider Dec. 11. The Bureau of Governmental Research issued a report Monday in which it supports a 20-year property tax that benefits...

BGR has released a new report that analyzes proposed 20-year property taxes for public libraries and housing that New Orleans voters will decide in the Dec. 11 election. The report is intended to help voters in New Orleans make...

Today, the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) releases a new report that analyzes proposed 20-year property taxes for public libraries and housing that New Orleans voters will decide in the December 11 election. Each tax would replace an existing...

After years of doing taxes the same way, Louisiana voters beginning Saturday are being asked to decide if the state should head in a different direction. Forty-three parishes, like Orleans, are choosing local leadership or deciding propositions, like East...

Three candidates have lined up to challenge longtime Orleans Parish Assessor Erroll Williams in this fall’s election. Anthony Brown, Carlos J. Hornbrook and Andrew “Low Tax” Gressett each blamed Williams for rising property assessments in the city, which have...

A tax agreement signed Thursday with the French Quarter Management District marked the final step toward resuming enhanced police patrols in the Vieux Carré and seemingly ended a contentious process over the past 1½ years. But the agreement includes...

NEW ORLEANS – From the Bureau of Governmental Research: Today, the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) published a new report raising concerns about the New Orleans City Council’s recent decision to exclude hotel room rentals from the sales tax...

In August, the New Orleans City Council excluded hotel room rentals from a new sales tax for enhanced public safety in the French Quarter despite questions about whether the exclusion is permissible under state law. While BGR has not...

A special sales tax to fund supplemental police patrols in the French Quarter will be reinstated starting in October after expiring at the end of 2020. The tax was approved by voters in an April ballot measure and was...

Orleans Parish voters will decide in November whether to renew two property taxes that expire at the end of the year — one for the public library system and another for affordable housing and blight initiatives. It appears likely...

A quarter-cent sales tax in the French Quarter, approved by residents of the historic neighborhood earlier this year through a ballot measure, was meant to go into effect on July 1. But that date has come and gone. And...

NEW ORLEANS (WVUE) – In order to fund the “Blue Light Patrols” in the Quarter, the reinstatement of the quarter-cent sales tax is back on the ballot after the initial renewal failed in December. Because of pandemic losses, the...

NEW ORLEANS – The Bureau of Governmental Research is weighing in against a proposition for a 0.245% sales tax to pay for supplemental police patrols and other public safety services in the French Quarter. The measure will go before...

NEW ORLEANS (WGNO)– For our viewers heading to the polls this weekend, there’s a new report out that you should know about before casting your ballot. The French Quarter Sales Tax is on Saturday’s ballot and the report from the Bureau of Governmental...

Today the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) releases On the Ballot: French Quarter Sales Tax, April 24, 2021. The report is intended to help French Quarter voters make an informed decision on a proposition to authorize a new 0.2495% sales...

Earlier this week, Mayor Cantrell’s Director of Strategic Initiatives Joshua Cox had a press conference wherein he accused the French Quarter Management District of not being able to administer their task force program, and of mismanaging funds. Newell invited...

The battle over security patrols in the French Quarter continues, with Mayor Cantrell’s administration remaining at odds with the French Quarter Management District (FQMD) on how previously-collected tax monies should be spent. The FQMD is currently responsible for funding...

A New Orleans City Council committee was set to consider Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s most recent nominee for the New Orleans Public Library Board of Directors on Thursday, but after an outpouring of public criticism, the nomination was put on...

NEW ORLEANS — A member of the New Orleans Public Library Board of Directors blasted the city’s library director at a board meeting Tuesday, accusing him of “spreading misinformation … and basically lies” about Proposition 2, Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s...

We find ourselves in the uncomfortable, but necessarily so, position of having to start this week’s Commentary with an apology. In late November, Gambit endorsed Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s millage proposals, most notably her controversial library millage plan. This was...

The voters in Orleans Parish spoke quite clearly Saturday when they rejected three millage proposals that Mayor LaToya Cantrell strongly pushed. I suspect the mayor isn’t hearing what they’re saying, at least not yet. There were plenty of complaints...

In Orleans Parish, multiple property tax measures were on the Dec. 5 ballot. New Orleans overwhelmingly rejected Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s near-term fiscal strategy Saturday when they voted down three property tax dedication changes as well as a French Quarter...

New Orleans voters roundly defeated all three of Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s tax proposals just days after she had warned that their failure could lead to the city implementing layoffs instead of the proposed furloughs that already figure to dramatically...

New Orleans voters on Saturday rejected a package of ballot propositions put forward by Mayor LaToya Cantrell that would have changed how the city spent roughly $23 million a year in property taxes. The plan would have cut roughly...

NEW ORLEANS — City leaders in New Orleans are calling on residents to approve three propositions on Saturday, which all deal with taxes set to expire at the end of next year. The first deals with funding infrastructure and...

ORLEANS PARISH, LA. — Orleans Parish voters will have to decide on three millage propositions at the polls. These propositions focus on infrastructure, housing and economic development, and early childhood education. New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell says voters need...

NEW ORLEANS — Facing significant opposition to her proposed cut to public libraries and to separate tax increases for infrastructure and economic development, Mayor LaToya Cantrell said Friday that if three propositions on Saturday’s ballot fail, she may have...

There are three parish-wide millage propositions on the ballot for Orleans Parish residents this weekend. One has to do with maintenance and infrastructure, another has to do with library funding and early childhood education. A third has to do...

New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell threatened to lay off city employees unless voters extend three property taxes Saturday. If the millages are not renewed, she said during a virtual town hall meeting Thursday evening, City Hall would “immediately have...

NEW ORLEANS — Saturday’s tax proposition in the French Quarter just picked up a heavyweight endorsement from one of the neighborhood’s most well-known residents. New Orleans entrepreneur Sidney Torres is financing a last-minute media campaign in support of the...

In Orleans Parish, multiple property tax measures are on the Dec. 5 ballot. Proposition 1 funds infrastructure, including roadwork. A yes vote for Proposition 1 would replace two existing property taxes with a new special tax. The existing millage...

NEW ORLEANS (WVUE) – Mayor LaToya Cantrell says there is a lot riding on three millages this Saturday. Proposition One is a renewal of a infrastructure and maintenance fund tax. Proposition Two is a restructured library tax which would...

Dr. Gabriel Morley, the director of the New Orleans Public Library, said at a Wednesday morning press conference that he had seen no written plan for how the library would adjust to a 40 percent budget cut being proposed...

Today the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) releases On the Ballot: French Quarter Sales Tax Renewal, December 5, 2020. The report is intended to help French Quarter voters make an informed decision on a proposition to renew a 0.2495%...

NEW ORLEANS— In addition to deciding the next district attorney, voters in Orleans Parish will decide issues that affect their wallets. There are three propositions the city is asking voters to renew. In an exclusive interview with WGNO News,...

The future of New Orleans’ publicly funded childcare program is now tied to a controversial tax proposal that slashes the library’s budget by 40 percent. Proposition 2 reduces the existing property tax dedicated to the city’s public library system,...

Newell talks to Research Director Stephen Stuart about what voters will see on their ballots in the Dec 5 election. The discussion focuses on the New Orleans property tax propositions on the ballot.

In recent weeks, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell has ramped up her campaign to convince voters to approve a plan to reallocate millions of dollars in property taxes, which will appear as three separate ballot propositions on the Dec....

New Orleans voters will be asked to reconfigure five soon-to-expire taxes into four new ones on the Dec. 5 ballot, leaving the overall tax rate the same but altering how much funding various city services and functions receive. The...

Mayor LaToya Cantrell is asking New Orleans voters to approve three interrelated millages on Dec. 5 that wouldn’t increase residents’ total tax bills, but would reallocate the proceeds for 20 years. The first would increase a combined streets and...

The diverse group of parents, librarians and concerned citizens that make up the Save Our Libraries coalition got a boost this week when the Bureau of Governmental Research added their voice to those opposing Proposition 2 which is on...

NEW ORLEANS — Early voting begins Friday across Louisiana for the Dec. 5 election, which includes the runoff for Orleans Parish District Attorney, as well as several judicial runoffs and important tax issues across the metro New Orleans area....

NEW ORLEANS – In a new report, the Bureau of Governmental Research – a private, nonprofit government watchdog – analyzes three separate propositions to replace several property taxes that will expire at the end of 2021. BGR said the...

In a report released Monday, the Bureau of Governmental Research, a local nonpartisan think tank, came out against a package of proposed property tax changes backed by New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell. Cantrell’s tax plan is being put to...

Today the Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) releases On the Ballot: New Orleans Property Tax Propositions, December 5, 2020. The report is intended to help New Orleans voters make an informed decision on three separate propositions to replace several City...

Over the past two years, thousands of homeowners across New Orleans have opened unwelcome letters from the Orleans Parish assessor’s office providing notice of big jumps in the assessed values of their properties and, with that, a sharp increase...

The Ernest N. Morial New Orleans Convention Center has spent $49 million of its large cash reserves to cover deep budget shortfalls caused by the coronavirus pandemic, which has ground the convention industry to a near-complete halt and starved...

The Orleans Parish Assessor Erroll Williams is responsible for determining the value of your real estate, your home and its improvements, and that creates a little of $600 million in property taxes to help finance the government – but...

At the request of Mayor LaToya Cantrell, the New Orleans City Council on Thursday gave final approval to a long-anticipated 6.75 percent tax on short-term rental bookings. Thursday’s ordinance codifying the new tax into city law comes more than...

NEW ORLEANS – Orleans Parish Assessor Erroll Williams is responsible for determining the value of more than 167,000 properties that are expected to create roughly $650 million in 2020 tax revenue. The office’s “open rolls” period lasts until Aug....

Members of the New Orleans City Council on Thursday initiated the process to renew a quarter percent sales tax in the French Quarter that has funded Louisiana State Police patrols in and around the French Quarter for the past...

Today, BGR published a new PolicyWatch newsletter, focusing on property assessment issues in New Orleans. Last year’s incomplete property reassessment in New Orleans led citizens and policymakers to question the progress made by the Orleans Parish Assessor on assessment system...

Today, BGR released the inaugural edition of PolicyWatch, a periodic newsletter that draws on BGR’s body of independent, nonpartisan research to address current public policy issues. This edition focuses on the City of New Orleans’ finances as it faces a...

A coalition of 21 local unions, advocacy organizations and other groups are calling on the Ernest N. Morial New Orleans Convention Center to release $100 million out of its unrestricted cash reserves to support hospitality industry workers who are...

The Ernest N. Morial Convention Center has presented a proposal to Mayor LaToya Cantrell to settle a yearlong dispute with the Regional Transit Authority over millions in tax dollars split between the two agencies and the New Orleans Tourism Marketing Corporation....

Having your car broken into via smashed windows has become the new normal in New Orleans. On Tuesday, Jan. 14, a group of neighborhood associations hosted a community meeting at the Jewish Community Center to “discuss the recent uptick...

Large portions of Convention Center Boulevard are closed for the entire month of December. It’s just the latest in a series of intermittent closures on the Central Business District thoroughfare as the street is permanently converted from four lanes...

Newell talks to BGR Vice President and Research Director Stephen Stuart and research analyst Jamie Parker about what’s changed since 2011, when New Orleans replaced the seven-assessor system with just one.

Property tax assessments in Orleans Parish have come a long way from the days when seven assessors with a mishmash of policies determined the value of properties across the city. And while Orleans Parish Assessor Erroll Williams has built...

The City Council has made a request to cut tax rates for property owners, and an agreement is under consideration. The plan is to move some individual millages around to prioritize infrastructure and public safety dollars over areas of...

Today, BGR releases Assessing the Assessor: Progress on Property Assessment Reform in New Orleans. The report evaluates whether and to what extent New Orleans’ property assessment system has improved under the single parish assessor since he replaced the seven-assessor...

Citizens in New Orleans who plan to vote in Saturday’s election can inform their decisions with BGR’s report, On the Ballot: New Orleans Bond and Tax Propositions, November 16, 2019. The report examines three separate propositions that would authorize...

On Friday, The New Orleans Tourism Marketing Corporation, a public municipal entity, provided some of the first details into what it will look like once the majority of its staff, mission and funding are absorbed by the private nonprofit...

Since taking office in May 2018, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell has searched far and wide for more money to fund the city’s pressing infrastructure needs, winning a big victory this spring when state officials and the tourism industry...

The topic of the Sewerage & Water Board of New Orleans is a contentious one. In the past two years, people have lost their homes and their vehicles due to the flooding of portions of the town. Yet, when...

As the New Orleans City Council reviews the proposed 2020 budget for the City of New Orleans, BGR presents here a collection of resources to help citizens understand the proposal in the context of recent City budget trends and...

November 16th, New Orleans residents will vote on three different propositions, all that would allow the city to use those dollars to improve local infrastructure. “This touches basic civics services, and if we want a better quality of life...

Today, BGR releases BGR Now: A Framework for Assessing New Orleans’ Proposed 2020 Budget, which outlines key findings of BGR’s recent City budget study and connects them to the current 2020 budget process to help inform citizens and policymakers....

In a report released Tuesday, the non-partisan Bureau for Governmental Research (BGR) has endorsed three ballot propositions that would collectively generate millions of dollars in both annual and one-time funding, most of which would be spent on infrastructure projects....

Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s top public works aides offered a roadmap Tuesday for the hundreds of millions of dollars they plan to spend on streets, drainage, parks and other infrastructure in coming years, even as they cautioned that much of...

In 2-1/2 weeks New Orleans voters will be asked to consider three new tax measures that city officials say, would generate more than $520 million a year for capital improvements and infrastructure needs. The Bureau of Governmental Research came...

The Bureau of Governmental Research is backing three ballot initiatives aimed at increasing city funding for infrastructure that Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s administration is putting before the voters on Nov. 16. Cantrell is asking voters to impose a new sales...

Today BGR releases On the Ballot: New Orleans Bond and Tax Propositions, November 16, 2019. The report analyzes three separate propositions that would authorize the City of New Orleans (City) to: Issue up to $500 million in bonds for...

One of the reasons you love Think504 is that we keep you informed about important political and civic decisions you have to make. So when you go into the voting booth (Early voting Nov 2-9 Election Day Nov 16) to elect...

Today, BGR releases A Look Back to Plan Ahead: Analyzing Past New Orleans Budgets to Guide Funding Priorities. The report reviews the City’s General Fund budgets from 2010 to 2019, focusing on growth in revenues and changes in expenditures. As...

Today, BGR releases On the Ballot: Housing Tax Exemptions in New Orleans, October 12, 2019. The report analyzes Constitutional Amendment No. 4, which voters will consider on October 12. It would allow the City of New Orleans to exempt from...

New Orleans will receive tens of millions of dollars to replace antiquated sewage pipes, fix faulty drainage pumps and mend pothole-filled roads, mostly by levying higher taxes on visitors, after the state Senate on Sunday gave final approval to...

For generations, the mayor of New Orleans was supposed to be a native, a smooth political operator and, it almost goes without saying, a man. In her history-making 2017 campaign, Mayor LaToya Cantrell bet that New Orleans was ready...

The city of New Orleans’ crumbling infrastructure will receive an infusion of tens of millions of dollars under a deal announced Monday by Gov. John Bel Edwards and Mayor LaToya Cantrell after weeks of hard-fought negotiations between their aides...

NEW ORLEANS (WVUE) – New Orleans voters approved a measure to consolidate taxes for the parish’s Parks and Recreation services Saturday (May 4). With 91 percent of precincts reported around 10:30 p.m., 76 percent voted to create the 20-year...

New Orleans voters approved a consolidation of soon-to-expire taxes for New Orleans parks and recreation organizations Saturday (May 4). The 20-year property tax will be split four ways among two city agencies and two park operations, including the first-ever local tax...

New Orleans voters on Saturday roundly endorsed a new financial plan for parks and recreation in the city that will boost services but not taxes. The overwhelming approval — about 76 percent — means the property taxes that benefit...

Voters in much of the New Orleans area will head to the polls Saturday to consider mainly requests involving taxes, as a parks and recreation tax in Orleans Parish, a teacher pay tax in Jefferson Parish and a school...

A measure to replace and redistribute expiring taxes for New Orleans parks and recreation organizations will be put to voters Saturday (May 4). If approved, the proposed 20-year property tax would be split four waysamong two city agencies and two park operations....

The closing of a deal to secure millions of dollars in immediate and continuing money for the city’s drainage infrastructure and the Sewerage & Water Board appears imminent for Mayor LaToya Cantrell. The negotiations in some respects could put more money in the hands of the...

Some very critical tax measures go before the voters on Saturday. Teacher pay raises and commitments to public greenspace and facilities in both Jefferson and Orleans. Even on the second Saturday of Jazz Fest, these millages are worthy of...

America faces a crisis at home more urgent than any before — other than Pearl Harbor and 9/11. That crisis is our crumbling and badly managed infrastructure. Some may call me an alarmist, but I don’t expect many New Orleanians...

Four years after calling for a comprehensive review of New Orleans’ tangle of tax dedications, the watchdog Bureau of Governmental Research has a new report that points out officials have done little to fix the problem. The nonprofit published...

The Bureau of Governmental Research is once again calling for changes in the way taxes are distributed in New Orleans, issuing a new report just as Mayor LaToya Cantrell and representatives of the tourism and hospitality industry are battling...

NEW ORLEANS (WVUE) – The Bureau of Governmental Research has released a report with updated estimates of how much money the City of New Orleans will generate from tax revenue this year. BGR released the report Thursday morning detailing...

Today, BGR releases The $1 Billion Question Revisited: Updating BGR’s 2015 Analysis of Orleans Parish Tax Revenues. With New Orleans facing billions of dollars in costs to improve infrastructure and public services, this report updates key figures from a 2015...

In a hardball move against the hospitality industry, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell took her fight for tourism tax dollars to the Louisiana Legislature Monday, with members of her administration testifying in favor of a series of bills to...

The Times-Picayune Editorial Board makes the following recommendation for the May 4 ballot. ORLEANS PARISH PARKS AND RECREATION TAX PROPOSITION To replace three existing property taxes for parks and recreation totaling 6.31 mills with a single tax at the...

Five years ago, with his request for a tax hike decisively rejected by voters, Ron Forman stood in an Audubon Commission conference room and promised to someday make taxpayer funding of “world-class attractions” like the Audubon Zoo easier for...

While it involves no new taxes, a proposition on the May 4 ballot will renew some existing property millages totaling 6.31 mills for parks and recreation in New Orleans. The three existing taxes will be renewed but distributed differently...

VOTERS IN NEW ORLEANS AND JEFFERSON PARISH WILL GO TO THE POLLS ON MAY 4 — during Jazz Fest — to consider several important property tax millages. In New Orleans, the sole item on the ballot is the proposed renewal...

The sole item on the May 4 ballot in New Orleans is a citywide referendum often referred to as “Parks and Rec.” The ballot proposition could just as easily be cast as a vote on the future of New...

On April 9, 2019, the independent Bureau of Governmental Research (BGR) released a report on the May 4 tax proposal that would replace three existing property taxes for parks and recreation with a single property tax at the same rate....

A nonpartisan research group is urging New Orleans and Jefferson Parish voters to support two tax measures that will be on the May 4 ballot. The private Bureau of Governmental Research announced Tuesday that it has endorsed a measure...

An independent New Orleans research group is backing the proposal to replace three existing property taxes into one millage for citywide parks and recreation. But there’s a caveat: If passed, the city is urged to monitor the park agencies’...

The Bureau of Governmental Research gave its blessing Tuesday (April 9) for a ballot proposal in New Orleans aimed at maintaining the current amount of property taxes charged for local parks and recreation services and a new split of...

Today, BGR releases On the Ballot: New Orleans Parks and Recreation Tax Proposal, May 4, 2019. The report analyzes a May 4 tax proposition in New Orleans to replace three existing taxes for parks and recreation totaling 6.31 mills with...

Hear WWL Radio’s Tommy Tucker talk with Amy Glovinsky, President/CEO BGR (Bureau of Governmental Research), about the City’s efforts to get a greater share of the tax revenue from the tourism industry. Click here to read BGR’s report on...

NEW ORLEANS (WVUE) – A last-ditch effort at the polls for a property tax to benefit elderly services fell flat Saturday (March 30). City Councilman Jason Williams sponsored the measure and posted on his Facebook page in the days...

New Orleans voters overwhelmingly rejected a new tax to pay for services for senior citizens Saturday in an election that doubled as a test of political might between Mayor LaToya Cantrell and the City Council. The more than 2-1...

New Orleans voters rejected a new property tax Saturday (March 30) to support elderly services, money the Council on Aging intended to use to shorten waitlists for its Meals on Wheels and housekeeping services programs. Unofficial results showed 12,335...

A property tax proposal on Saturday’s (March 30) ballot to support elderly services in New Orleans has given Mayor LaToya Cantrell a platform to call for more accountability and transparency from agencies not under City Hall control. Yet the...

In a video posted to Facebook earlier this week, Mayor LaToya Cantrell continued to urge New Orleans residents to vote “NO” on a new property tax. The proposed tax increase would be sent to the Council on Aging, a...

The Times-Picayune Editorial Board makes the following recommendation for Saturday’s election (March 30). ORLEANS PARISH Elderly Services Tax Proposition To levy a 2-mill property tax for five years for services for senior citizens No It’s clear that New Orleans...

NEW ORLEANS — Suppose we had an election and almost no one showed up? That could happen this Saturday in New Orleans — and it could raise your taxes. That’s the topic of this week’s commentary by Eyewitness News Political...

VOTE YES in the upcoming 2 Mills, Senior Services Property Tax Special Election on March 30. Funding for senior services has collapsed in Orleans Parish post-Katrina, and the dollars allocated out of the General Fund proved pretty anemic prior to...

It’s 2019, but looking at some of the city’s old and antiquated infrastructure, it doesn’t feel like it. We have a pumping system that includes parts that are over a hundred years old, and a water and sewer system...

Before the fish plates were served Friday at the senior center on the edge of Pontchartrain Park, Joyce Rawlins and Rose George were on opposite sides of a debate. Rawlins, 73, supported giving the organization that manages the center...

We don’t want to disrespect our elders, but a proposal to levy a new 2-mill property tax in New Orleans for elderly services is not the show of respect that our seniors deserve. The proposition is the only item...

NEW ORLEANS (WVUE) – On March 30th voters in New Orleans will decide whether to pass a property tax to benefit senior services — a measure that has not been as well-received as some had hoped. According to the...

Less than a month away from the start of the 2019 legislative session, Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s legislative agenda is being shaped by her push to divert millions of tax dollars from state-sponsored tourism and sports agencies to helping meet New...

The Great Hall of the New Orleans Ernest N. Morial Convention Center was a bustle of activity the day before 18,000 cardiologists from all over the world were set to arrive for their annual gathering. Electricians tinkered with video...